Peter Bogdanovich, in an article published in Esquire, in October 1972, entitled The Kane Mutiny, responds to Kael, and maintains that he has interviewed Welles himself and clarified the points that she has managed to misinform, especially since the relationship of the famous filmmaker with Mankiewicz. That is, in her analysis, she highlights the importance of contexts, but also because she concludes that Kane is, above all, a parody of a journalism mogul, an ironic story about the national.

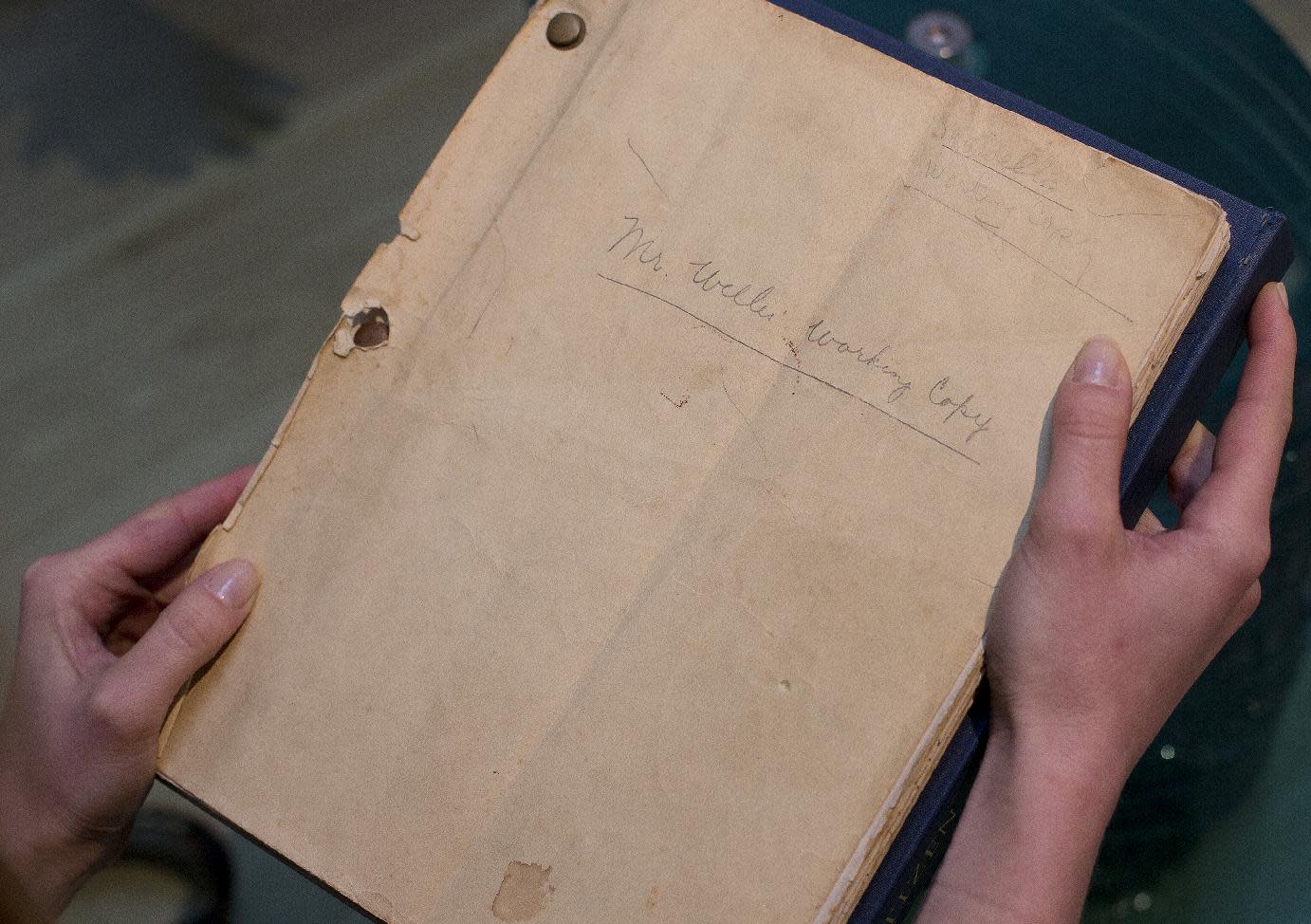

Was this first Welles film, a work of authorship?īeyond this problem that Kael establishes, his text remains as a great conjunction of cinephile frenzy, of appointments, of relationships about the world of journalism, millionaire production, the environment of the scriptwriters, the love of theater seen as cinema, and Hollywood’s overwhelming and mercantile system. Mankiewicz (who had worked with Josef von Sternberg or the Marx Brothers) and questions some decisions of style, staging, and context attributed – and assumed – by Welles. In that text, Kael maintains, in order to go against the defenders of the so-called policy of the authors, that Welles was not the absolute author of Citizen Kane, and that the weight of authorship falls on the figure of the renowned screenwriter Herman J. Her research was easily disproved by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich and the critic, her great opponent, Andrew Sarris. In her famous two-part 1971 article Raising Kane, American film critic Pauline Kael rants against Orson Welles’ outright authorship in Citizen Kane, the tip of the canon of film history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)